Mt Lassen-10,328' (Lassen Peak)

(40.4876594, -121.5049807) Note: the high peak is 10,457'

|

| From Up and Down California by William Brewer

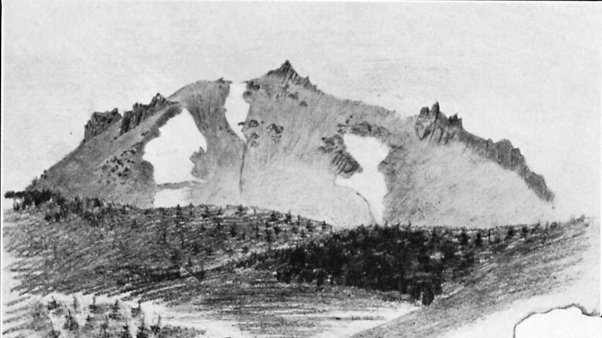

LASSEN PEAK From a sketch by Clarence King |

While waiting for breakfast, which we got at a neighboring house, we had a most glorious sunrise, the sun rising directly beyond the high, snow-covered Lassen’s Butte. The peak was gloriously illuminated. From Up and Down California: The Journal of William H. Brewer, 1860-1864, Book III, Chpt 4

As we struck this we came in sight of Lassen’s Peak, rising gloriously, scarcely forty miles distant, a grand object indeed. We camped by the Feather River, here a large, cold stream, abounding in trout. The night was intensely clear, and the temperature sank to 20°. There is a store here and we laid in more provisions, for it is the last we shall find for many a weary mile. September 22 we came on toward Lassen’s Peak, some twenty-two miles farther. First, for fifteen miles, we followed up the valley, the Big Meadows, a level valley with high mountains on all sides; but the grand feature is Lassen’s Peak, rising beyond the head of the valley. In front, the level meadow; then the dark forests along the base of the mountain; while beyond, and above all, rises the bare and desolate peak of snow and rocks, against the blue sky, which is streaked here and there with thin clouds. From Book 4, Chpt 6. September 26 we made our first ascent of Lassen’s Peak—King and I and the three friends who had come with us from their camp. We were up and off early, were on the summit before ten o’clock, and spent five hours there. We had anticipated a grand view, the finest in the state, and it fully equaled our expectations, but the peak is not so high as we estimated, being only about 11,000 feet.5 The day was not entirely favorable—a fierce wind, raw and chilly, swept over the summit, making our very bones shiver. Clouds hung over a part of the landscape. Mount Shasta, eighty miles distant, rose clear and sharp against a blue sky, the top for six thousand feet rising above a stratum of clouds that hid the base. It was grand. Most of the clouds lay below us at the north. The great valley was very indistinct in the haze at the south, but the northern part was very clear. From Book 4, Chpt 6. The description that follows I wrote on top of the mountain. It has the merit of rigid truthfulness in every particular. First up a canyon for a thousand feet, then among rocks and over snow, crisp in the cold air, glittering in the bright moonlight. At four we are on the last slope, a steep ridge, now on loose bowlders and sliding gravel, now on firmer footing. We avoid the snow slopes—they are too steep to climb without cutting our way by steps. We are on the south side of the peak, and the vast region in the southeast lies dim in the soft light of the moon—valleys asleep in beds of vapor, mountains dark and shadowy. At 4.30 appears the first faint line of red in the east, which gradually widens and becomes a livid arch as we toil up the last steep slope. We reach the first summit, and the northern scene comes in view. The snows of Mount Shasta are still indistinct in the dusky dawn. We cross a snow field, climb up bowlders, and are soon on the highest pinnacle of rock. It is still, cold, and intensely clear. The temperature rises to 25°—it has been 18°. The arch of dawn rises and spreads along the distant eastern horizon. Its rosy light gilds the cone of red cinders across the crater from where we are. Mount Shasta comes out clear and well defined; the gray twilight bathing the dark mountains below grows warmer and lighter, the moon and stars fade, the shadowy mountain forms rapidly assume distinct shapes, and day comes on apace. As we gaze in rapture, the sun comes on the scene, and as it rises, its disk flattened by atmospheric refraction, it gilds the peaks one after another, and at this moment the field of view is wider than at any time later in the day. The Marysville Buttes rise from the vapory plain, islands in a distant ocean of smoke, while far beyond appear the dim outlines of Mount Diablo and Mount Hamilton, the latter 240 miles distant. North of the Bay of San Francisco the Coast Range is clear and distinct, from Napa north to the Salmon Mountains near the Klamath River. Mount St. Helena, Mount St. John, Yalloballey, Bullet Chup, and all its other prominent peaks are in distinct view, rising in altitude as we look north. But rising high above all is the conical shadow of the peak we are on, projected in the air, a distinct form of cobalt blue on a ground of lighter haze, its top as sharp and its outlines as well defined as are those of the peak itself-a gigantic spectral mountain, projected so high in the air that it seems far higher than the original mountain itself—but, as the sun rises, the mountain sinks into the valley, and, like a ghost, fades away at the sight of the sun. The snows of the Salmon Mountains glitter in the morning sun, a hundred miles distant. But the great feature is the sublime form of Mount Shasta towering above its neighboring mountains—truly a monarch of the hills. It has received some snow in the late storms, and the “snow line” is as sharply defined and as level as if the surface of an ocean had cut it against the mountain side. Through the gaps we catch glimpses of the Siskiyou Mountains, and, east of Mount Shasta, the mere summits of some of the higher snow mountains of Oregon. In the northeast is the beautiful valley of Pit River, with several sharp volcanic cones rising from it; while chain appears beyond chain in the dim distance, whose locality I cannot say, for we have no maps of that region. In the east, valley and mountain chain alternate until all becomes indistinct in the blue distance. The peaks about Pyramid Lake are plainly seen. Honey Lake glistens in the morning sun—it seems quite near. In the southeast we look along the line of the Sierra, peak beyond peak, until those near Lake Bigler form the horizon. The mere summit of Pyramid Peak is visible, but the Yuba Buttes, Pilot Peak, and a legion of lesser heights are very distinct. The valleys between these peaks are bathed in smoke. Nearer, in this direction, are several beautiful valleys—Indian Valley, the Big Meadows, Mountain Meadows, and others—but all are dry and brown. Like many philanthropists, in looking at the distant view I have almost forgotten that nearer home, just about the peak itself. Great tables of lava form the characteristic features; for Lassen’s Peak, like Mount Shasta, is an extinct volcano. The remains of a crater exist, a hollow in the center, with three or four peaks, or cones, rising around it. The one we are on is the highest. The west cone has many red cinders, and looks red and scorched. A few miles north of the peak are four cones, the highest above nine thousand feet high, entirely destitute of all vegetation, scorched and broken. The highest is said to have been active in 1857. The lava tables beneath are covered with dark pine forests, here and there furrowed into deep canyons or rising into mountains, with pretty valleys hidden between. Several lower peaks about us are spotted with fields of snow, still clean and white, sometimes of rose color with the red microscopic plant, as in the arctic regions. Little lakes bask in the sunlight here and there, as blue as the sky above them. Twelve are in sight. And the Boiling Lake is in view, with clouds of white steam rising through the trees in the clear, cold, mountain air. Here and there from the dark forest of pines that forms the carpet of the hills curls the smoke from some hunter’s camp or Indian’s fire. Many volcanic cones rise, sharp and steep, some with craters in their tops, into which we can see—circular hollows, like great nests of fabulous birds. On the west, the volcanic tables slope to the great central valley. The northern part of this, from Tehama to Shasta City, is very distinct and clear, with its forests and farms and orchards and villages, a line of willows marking the course of the Sacramento River. Farther south, smoke and haze obscure the plain. But in all this wide view there appear no green pastures or lovely green herbage. Dark green forests, almost black, lie beneath us; desolate slopes, with snow and scattered trees, lie around us, and all the valleys are dry and sere. All is as unlike the mountains of the eastern states, or the Alps, as it is possible for one mountain scene to be unlike another. As the sun rises it is truly wonderful how distinct Mount Shasta is. Its every ridge and canyon and snow field look so plain that one can scarcely believe that it lies eighty miles distant in air line—a weary way and much farther by any road or trail. The valleys become more smoky, and the distant Sierra more indistinct, dark and jagged lines rising above the haze. Until 10 A.M. not a cloud obscures the sky, then graceful cirri creep over from the Pacific, light and feathery. The day wears on. The sun is warm and the air balmy. Silence broods over the peak—no sound falls on the ear, save occasionally, when a rock, loosed by last night’s frost and freed by the day’s thaw, rumbles down the steep slope, and all is silent again. Now and then a butterfly or bird (of artic species) flits over the summit and among the rocks, but both are silent. Before 2 P.M. the smoke increases in the valleys, until the great central valley looks like an indistinct ocean, without surface or shores. Mountain valleys become depths of smoke that the sight cannot penetrate. The distant views fade away in haze, and the landscape looks dreamy. We remained on the top until nearly three—over nine hours—then returned. We enjoyed a slide down a steep slope of snow. I “timed” King on it—he descended a slope four hundred or five hundred feet in fifty-seven seconds. The only mishap of the day was King getting his ears frostbitten. From Up and Down California by William Brewer, Book 4 Chapter 6

October

9 we came on to Deer Creek, Lassen’s old ranch, originally owned by the

man2 whose name is given to Lassen’s Peak. He was murdered about two

years ago by the Indians. From Up and Down California: The Journal of William H. Brewer, 1860-1864, Book III, Chpt 6

2.

Peter Lassen, born in Denmark in 1800, came to America in 1829. After a

residence of ten years in Missouri he emigrated to Oregon and the

following year came to California by boat. In 1843, while working for

Sutter, Lassen became familiar with the Sacramento Valley. He applied to

the governor for a grant of land on Deer Creek and became one of the

first settlers north of Sacramento. Returning from a visit to Missouri

in 1848 he brought the first Masonic charter to California. Lassen later

sold his Deer Creek ranch and moved to Plumas County, where, in April,

1859, he was killed by Indians. Lassen Peak and Lassen County are named

for him. The name was commonly pronounced “Lawson,” judging from

contemporary spelling. From Up and Down California: The Journal of William H. Brewer, 1860-1864, Footnote, Book III, Chpt 6

From GNIS:

From GNIS:

- In Lassen Volcanic National Park, 1.9 km ( north of Mount Helen and 1.9 km (1.2 mi) south-southwest of Crescent Crater.

- Named for early explorer Peter Lassen.

- Also called:

- Lassen Buttes: Harris, Lola. Place Names of Eastern Shasta County. Redding, California: Shasta College, 1967. p10

- Lassen's Butte

- Lassen's Peak:

- Lassens Buttes: Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1949. p183

- Lawson's Peak:

- Mount Joseph: Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1949. p183

- Mount Lassen: U.S. Geological Survey. Geographic Names Phase I data compilation (1976-1981). 31-Dec-1981. Primarily from U.S. Geological Survey 1:24,000-scale topographic maps (or 1:25K, Puerto Rico 1:20K) and from U.S. Board on Geographic Names files. In some instances, from 1:62,500 scale or 1:250,000 scale maps.

- Mount Saint Jose: Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1949. p183

- Mount Saint Joseph: Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1949. p183

- San Jose *: The American Guide Series, Compiled and Written by the Federal Writers' Project of the Work Projects Administration. A state by state guide series published by various publishers, in the late 1930's and 1940's. Each book studies and describes each state's history, natural endowments, and special interests. Use code US-T125/Name/YYYY/p#. California/p504

- Snow Butte: Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1949. p183

- Snow Mountain: Harris, Lola. Place Names of Eastern Shasta County. Redding, California: Shasta College, 1967. p10

Trips:

- July 25, 2015 - Meetup hike up Lassen Peak

- July 26, 2015 - Return trip with John and Cathey

References:

- Wikipedia

- NPS trail description

- NPS: Erruption of Mt Lassen

- Wired 100 year retrospective

- USGS Volcanic Hazards

- USGS Fact sheet

No comments:

Post a Comment